By John Durkacz

It is postulated that the honey bee was pushed south by the advancing ice caps towards the Mediterranean region and extreme south western France during the last ice age. These surviving populations then slowly moved northwards following the receding ice as the climate warmed again and were able to cross the land bridge which existed around 8,000 years ago into what are now the British Isles. We can only guess how honey bees lived before man began to substantially alter the landscape by forest clearance. The Scottish climate and landscape has always been marginal for honey bees though the central and eastern areas were more suitable.

The central lowlands and eastern parts were the most fertile and there is evidence of beekeeping associated with the monastic houses and abbeys from the north east to the borders. The bee boles register (International Bee Research Association) shows the majority of bee boles situated in the east in those most fertile regions with lower rainfall; the largest number in Tayside, Fife and the Lothians. Many lesser known bee boles were identified by beekeepers in Fife and Dundee areas and it is likely that many will have disappeared by now. They are a testimony to the integral part that honey bees played in our rural economy in the past. We should not ignore that bee boles of a much simpler design were also widespread in smallholdings in the north east and often went unrecognised.

Easter Lynne, Stratha’an.

Abandoned WBC and Cottage hive with roughly constructed wall with old bee boles for housing skeps. I found several of these in old farms and cottages in the north-east Highlands where I kept bees for many years. Many were sadly neglected and are likely to be lost by now.

Photo: John Durkacz

Beekeeping became an important part of rural activities during the 19th century when skeps were used, protected from our changeable weather in bee boles. The indications are that numbers of colonies fluctuated considerably depending on the seasons. Also many beekeepers were importing queens and small colonies from the continent in the belief these were more productive and in many cases easier to handle than the unimproved local bees. Even by the end of the 19th century there were comments by Scottish beekeepers that the true native black bee was becoming more difficult to find.

In the early years of the 20th century there were continuing importations of bees but it is likely that in remoter areas beekeepers continued to use the native bee but there is also evidence of dispute about what bee was ‘best’. Some were saying that anything was better than the common black variety and others strongly supported the native dark bee voicing concerns about the wintering ability of imported bees. By 1912 the Isle of Wight epidemic had reached Speyside. The ‘Scottish Beekeeper’ reported a ‘terrible year’ with a ‘wet and sunless summer’ and whole apiaries wiped out.

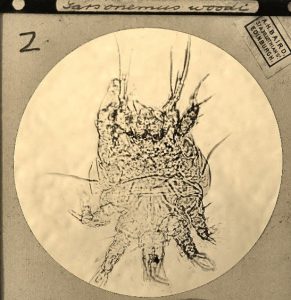

Original slide of the acarine mite or Tarsonemus woodi as it was then known. Dr John Rennie’s work was funded by AHE Wood (Glassel House, Aberdeenshire) and his researches led to the discovery of this tracheal mite which was found in all the samples from colonies affected. Much later work suggested that transmission of viral disease was the cause of the devastation.

Photo: from old glass slide in SBA archives

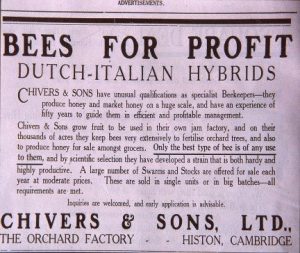

After 1912 the IoW disease swept through the north on several occasions and around 80% of colonies were lost but there were survivors. Adverts in the Scottish Beekeeper show where replacement imported colonies came from but these were not all Italian as many dark bees were imported from France and Holland.

Scottish Beekeeper ads

During the interwar years beekeeping remained an important part of the rural economy and many experts in the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association worked hard and travelled widely supporting beekeepers and helping in the transition from skep to modern beekeeping methods. The college advisory services played an important role here. Dr John Anderson in the North of Scotland College of Agriculture was a hugely important figure and under his influence the number of beekeepers rose dramatically. DM McDonald from Ballindalloch was just one notable expert who travelled widely in the North East supporting beekeepers through these difficult times. But later in the more distant areas the number of beekeepers fluctuated and declined as depopulation of the rural areas began. I managed to interview two elderly farmers in the Stratha’an area many years ago. They were Mr McArthur from ‘The Knock’ and Paddy MacDonald from ‘Inverchor’ and both had small commercial beekeeping interests in their younger days.

Paddy MacDonald had around 100 colonies using Italian bees in the low- lying areas and black bees near his hill farm which was in a remote area. He had his own waxed cartons for run honey and specialized in comb honey.

Photo: J Durkacz from original documents

Mr McArthur’s apiary in Stratha’an after he gave up active beekeeping. One of these hives had a strong colony of dark native bees which I was able to transfer.

Photo: John Durkacz

Moving to the Borders we find major beekeepers running commercial enterprises successfully who did so using local native bees which they were able to select and improve. Willie Smith from Innerleithen began his beekeeping after the 1st World War eventually running around 150 colonies as a single-handed full-time commercial venture. In the later 1920s he developed a single-walled hive with short frame lugs and top bee space later to become the ‘Smith Hive’ which was widely adopted in Scotland. He was probably the first full-time commercial beekeeper in Scotland and much revered and his advice sought after. He used locally sourced native bees as did later beekeepers in the area, Willie Robson from Chainbridge and George Hood from Ormiston (East Lothians).

Willie Smith, probably Scotland’s first full-time commercial beekeeper. After he retired from beekeeping many of his hives went to George Hood and others to local beekeepers. Subsequent surveys have confirmed a higher concentration of native dark bees in the borders area.

Archive photo: permission of Morna Stoakley and Amanda Clydesdale

In the 1970s and 80s in the north at Craibstone, Bernhard Möbus became a popular beekeeping advisor and champion of our native honey bees. Bernhard wrote widely on the effects of Varroa (which at that time had not reached our shores), bee breeding and the use of small mating nucs. He also researched wintering abilities of honey bees and the effects of winter brood rearing and presented his papers at Apimondia. He recognised the need to have a bee that was adapted to Scottish conditions, was docile and could winter well. He discovered colonies belonging to an elderly beekeeper in the village of Maud (Aberdeenshire) which fitted the required characteristics and raised numerous queens which were spread around Scotland. Descendants from these colonies are still to be found.

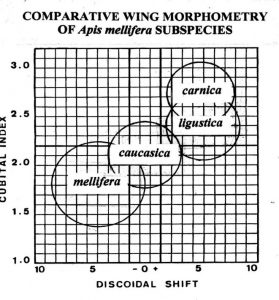

John and Morna Stoakley were keen beekeepers who moved to Scotland in 1968. They soon discovered that local bees were the best for their apiaries near Peebles and were inspired by Bernhard Möbus’ teaching. They had strong connections with the SBA and BIBBA and started bee improvement classes teaching BIBBA developed selection procedures for the native honey bee. These early classes were held in a rural primary school in Stobo and attracted excellent teachers through BIBBA for wing morphometry classes. They were also involved with the organisation of the joint SBA/BIBBA 1992 conference ‘Northern Bees in the 90s’ held in St Andrews. John was an entomologist by profession working for the Forestry Commission and well versed in procedures for surveying insect populations. By 1994 they had completed a wing morphometry survey from apiaries in Scotland which showed that ⅓ rd of colonies were native honey bees, ⅓ rd ‘near natives’ and the remainder hybridised. This confirmed there were significant surviving populations of native dark bees despite continuing importations.

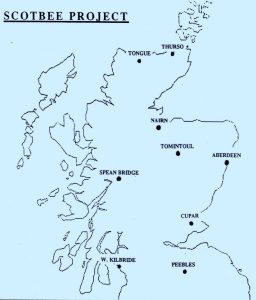

Colony samples were taken from apiaries including Peebles and Central belt not shown on this map. The apiaries had around 10 colonies each and the sampling was done randomly from these apiaries. Measurements were made manually for discoidal shift and cubital index and plotted to show distribution.

Summary of results

⅓ of colonies were Apis mellifera mellifera

⅓ were ‘near natives’

⅓ appeared to be hybrids

Data for the first two groups showed a continuous distribution

No evidence of regional differences

The untimely death of John Stoakley and the closure of Craibstone with the departure of Bernhard Möbus were serious blows for the conservation of Scottish native honey bees but the ‘Maud’ strain had already been widely dispersed. Bernhard wrote about his work in the college journal where he described the rearing of his preferred strain and there are confirmatory articles in the ‘Scottish Beekeeper’ explaining how associations visited Craibstone and many young queens were collected by members. A more recent survey involving samples from another survey (Ewan Campbell, Aberdeen University with Jim McCulloch) where DrawWing was used for morphometry checks showed very similar results to those from the Stoakley survey.

Despite the even heavier importations of foreign bees over the past few years there is good evidence that the native bee survives in Scotland. Europe wide studies confirm that locally adapted bees survived longer. The native bee is able to respond more readily to local forage and climate changes holding back on brood rearing and storing large amounts of pollen and has better wintering abilities. This enabled survival during periods of neglect in beekeeping when economic depression led to periods of depopulation and a reduction in numbers of beekeepers in many areas of Scotland.

John Durkacz

2017